In The Road to Mastery, I discussed some of the mental blocks and physical backslides I’ve experienced over the years. That road is never a straight line because progress isn’t linear. In this post, I will discuss strategical fear management to support our Geriatric Gymnast training. (Hint: train smarter, not harder.)

Original post: January 2022. Edited: June 2025

Fear is a natural, powerful, and primitive human emotion. It involves a universal biochemical response as well as a high individual emotional response. Fear alerts us to the presence of danger or the threat of harm, whether that danger is physical or psychological.

Lisa Fritscher, Verywellmind.com

Fear is a very real and pervasive experience in adult gymnastics, and with good reason. After all, we are trying to accomplish things that, from an ageist perspective, we have no business trying to do.

It’s all chemical

When we experience fear, strong physical reactions occur.

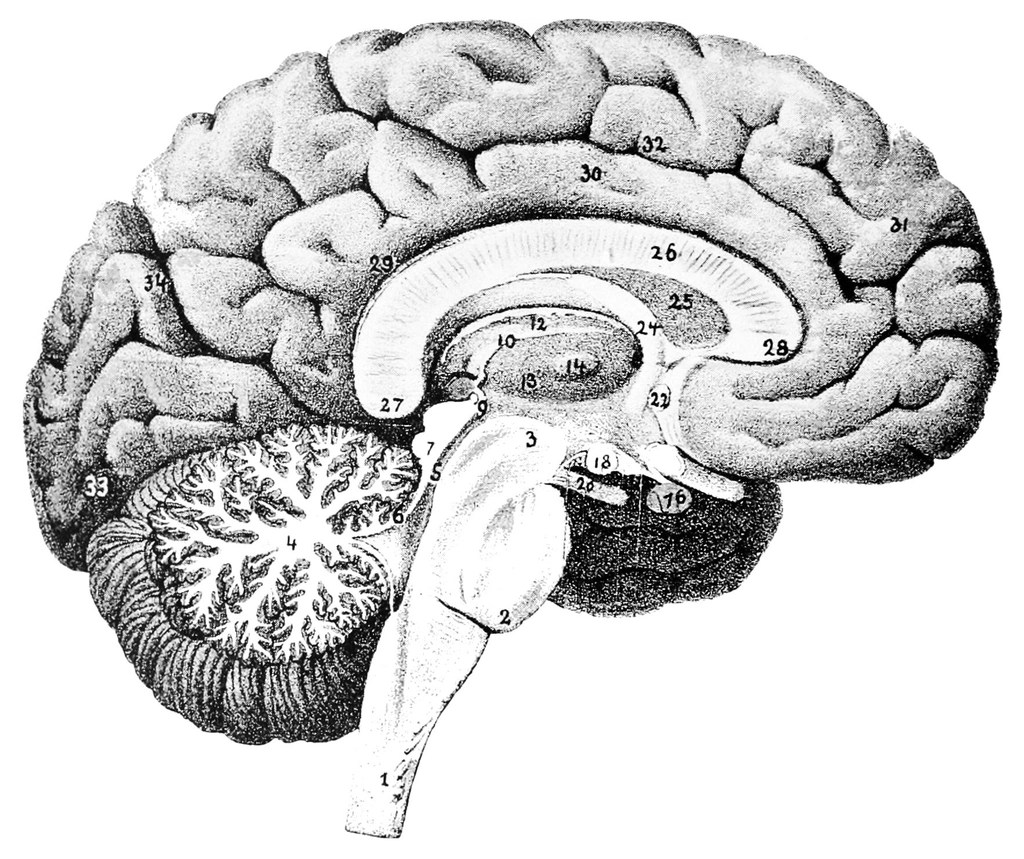

It starts in the tiny, almond-shaped amygdala. It’s nestled deep in the underside of the brain, near the top of the brain stem.

The amygdala is part of the limbic system, which controls emotions, memory, motivation and behavior. It triggers the nervous system to release both adrenaline (fight or flight hormone) and cortisol (our stress hormone). Our heightened senses suddenly raise our heartbeat and respiration. Our bodies are preparing us to fight or to run for our lives. It’s the natural activity in our bodies that teaches us to keep ourselves safe and out of harm’s way. Humans have survived saber-tooth tigers and wild boars because of it.

WebMD explains things in more detail.

How the amygdala steers us in the gym

In the gym, a healthy dose of fear is what keep us from facing imminent disaster. I can’t tell you how often I have felt my heart racing. I feel it when I’m about to try something new, difficult, or attempting something that isn’t familiar enough to me. At least once every time I go to train, I get that twinge in my chest and gut.

There’s always a skill that I’m working on that makes me uncomfortable. My amygdala reminds me to take a moment, draw a breath, and pay attention before hurtling my body into space.

This is the plight of the avid adult gymnast who didn’t flip as a kid. Our brains have much more cognitive development than children. This creates an over-developed fear factor. Understandably so, and it is enough to prevent most adults from even stepping foot on a gym floor.

However, when you do allow yourself to start training as an adult, the flood gates open wide. You start to gain some fundamental skills. The feel-good hormones: dopamine, serotonin, endorphins and oxytocin all kick in. You feel a little like a superhero and all you want to do is to learn more cool flippy stuff. Your brain engages in a battle between abject fear and desiring more success.

I remember when I first started my gymnastics training at 36. (I am a gymnastics addict has that story). Just bouncing on the trampoline and trying to stay upright was a challenge. Women my age and older were doing complex tumbling passes, vaulting handsprings over towers of mats, and chucking back flips on the floor. My brain went into overdrive as my inner child screamed “I WANNA DO THAT TOO!!” I wanted to feel like I could fly.

From that point forward, every training day was an education in balancing fear with action.

The difference between kids and adults

As a child, your skeleton is still basically made of rubber. Falling off of a balance beam or landing poorly on a tumbling pass is par for the course. As long as you know how to fall and there’s enough padding to cushion it, the fear factor is manageable. Of course, kids do experience fear. They usually get over it pretty quickly once they see that they can safely accomplish something. The fear melts away and they act like lunatic monkeys to keep doing that thing.

Case in point: I once subbed for an advanced class of 8-14 year olds. They worked on improving some of their existing skills. I noticed that as these kids absorbed bits of coaching advice, they managed their fears easily. They could apply a few minor corrections that helped them land on their feet more consistently. Then, like adrenaline junkies, they were eager to repeat that skill over and over again. True Energizer bunnies.

Adults have a limited reserve of physical energy. We don’t have the endurance to practicing something over and over again. We don’t get the same neurological reinforcement that benefits the kids. Thus, our progress is always much, much slower.

As adults, even when there’s proof that you can do a skill, the amygdala still goes into overdrive. It knows that adults are not made of rubber, so there’s greater risk potential. One wrong angle or motion can make a world of hurt for us. Our recovery time is also much, much longer if we do get hurt

With that in mind, there’s another big difference between chronological children and adults who want to play like children. Big kids have family and work responsibilities, more fragile bones, and joints that creak and moan just by standing up. We have no choice but to think twice about participating in physically risky behaviors. The fear factor rises exponentially. The last thing an adult needs is to damage ourselves during our recreational activities. That might prevent us from being able to execute our regular adult responsibilities.

Therefore, Geriatric Gymnasts must use our wise minds while training. Finding a safe balance between stretching our limits and knowing when to pause is a delicate balance, indeed.

Simone’s example of using her wise mind

I can only imagine what Simone Biles was thinking when she suffered a serious case of the “twisties”. She completely lost her bearings during her last Amanar vault during the 2021 Olympic team final. Instead of the two-and-a-half twists that she had planned, she lost her way midair, completed one-and-a-half instead, and unexpectedly stumbled out of the landing. The wave of fear she experienced in that split second stopped her in her tracks.

Thankfully, Simone had the skill to get herself safely to the ground so she didn’t actually kill herself. However, the experience rattled her enough that she made the impossible decision to pull herself out of the competition altogether. She needed to figure out what went wrong. She knew that “shaking it off” and proceeding could have resulted in serious damage. Instead, her amygdala activated her self-protective mechanism. Fortunately, she had the presence of mind to acknowledge it on an international stage.

In my eyes (and to most gymnasts out there), she’s a hero and an extraordinary role model. I strive to follow her lead in my own adult training. In the elite domain, where the skills are off the charts, smart athletes know how to strike a balance. They navigate the experience of fear by wisely breaking through it to achieve new levels of mastery.

Using fear as a guide

I can’t tell you how many injuries I’ve sustained because I thinking like the child. Sometimes, my brain was too eager to acquire new skills before my body was ready to do so. Other times, I’ve do one too many repetitions with bad form or when I was too tired. Sometimes, things just happened.

My running list of injuries: stubbed toes, bruised shins, sprained ankles, broken bones, plantar fasciitis flares, shin splints, rotator cuff tears, Achilles rupture. Unfortunately, it’s a long list.

With gymnastics, it seems inevitable that some injury will happen. I have learned, sometimes the hard way, to use fear as a cautionary guide. After each recovery, there is a lingering layer of vigilance. It is not enough to stop me, but I’ve learned to press the pause button earlier. Impulsivity is the antithesis of safe Geriatric Gymnast training.

The answer is to train smarter, not harder (another favorite phrase of mine).

Putting excessive physical effort into a workout can have negative repercussions for a long time. To be sure, the balancing act between caution and action is a continuum of wise effort. Like walking a tightrope (or balance beam), we mindfully proceed with wobbly and corrective steps.

These are three of my hard-learned Geriatric Gymnast wise-mind lessons

LESSON ONE: Staying mindful

The venture into adult gymnastics requires mindful presence to make that balance happen. It has taught me to think step-by-step and in the moment.

Be where you are is one of my favorite phrases. I don’t remember exactly when this phrase came into my life, but it has become the cornerstone of my training.

The benefit of this phrase is that it helps to focus my attention and stare Mr. Lizard square in his beady little eyes.

Be where you are simply means this: focus on what’s in right front of you, not something three steps away. In a tumbling pass, you must successfully complete one move before you can start the next. The first sets up the second. If your attention is too far ahead, you risk executing poor technique on your setup. This messes up the entire system and puts you at more risk.

Mindfulness plays a huge role in the training rituals of the adult gymnast. Often, lower extremity injuries happen just by mindlessly stepping on a different or less stable surface. This happens in the gym more often than you’d think.

How many times have I stubbed my toe or rolled my ankle moving from one surface to another? I once sprained my ankle stepping into a simple, slow roundoff on the TumblTrak. The injury wasn’t even on the landing; it was on the takeoff. Anyone who has sprained an ankle knows that it doesn’t heal quickly. For me, my day job as a dance teacher was made much more challenging hobbling around in an air cast.

LESSON TWO: Navigate everything carefully

Nowadays, I am much more cautious and mindful moving from place to place in the gym.

- Start slowly: No matter how fundamental the skill, I always take my time. Once I know how my body system is responding, I can decide how hard I want to push that day. Believe me, the few extra moments of forethought are worth it if you walk out of the gym uninjured.

- Long, deliberate warm ups: Adults need more warm up time on every surface before we dive into the real flippy fun. This is both for mental and physical readiness.

- Testing surfaces: I’ll always take a moment to test out how different surfaces feel on my joints at that moment. The first bounce of the day always feels crunchy. Suddenly changing surfaces can be fraught with peril. I always look where I’m stepping and think about what each step will feel like before I proceed.

- Mental planning and visualization: Even if I’ve completely mastered a skill, I still plan mentally. Before diving in, I imagine what the skill looks like from beginning to end. This is a favorite technique of elite gymnasts as well.

- Short turns: When I do finally get into the thick of doing skills, I don’t belabor them. I take short turns, then stop to process what just happened. I’ve found that taking excessively long turns or doing too many repetitions only reinforces bad form. Pushing past fatigue is counter-productive. Three great rounds is better than ten sub-par ones.

LESSON THREE: Listen to your gut

Part of the process is learning to embrace the fear, put it in its proper place and using it wisely. It’s like a regular sounding board that you need to listen to.

Years ago, I was working on standing back tucks off of a short tower of mats. One day, we set up the station, and I chucked my first one. I probably under-rotated and landed on all fours. I decided to work on a trampoline drill, hoping to improve my rotation and transfer it to the mat stack. It didn’t help the way I had hoped. I under-rotated the move and landed safely, but not on my feet.

I was set to try again, and I got that familiar, fluttery feeling. I knew it was time to stop. Something wasn’t right. I was tired, I didn’t have the energy or power to land properly, and I felt slower than usual. All told, I listened to my gut. That skill was a wrap for the day and I moved on to something else.

No harm, no foul, no injury. There’s always next time.

When you listen to your gut, which is dutifully informed by that almond-shaped amygdala, you can stay safe as you work on pushing your limits. It certainly takes patience; the frustration of not being able to perform a skill can be overwhelming. It takes thinking like an adult.

Like the GOAT taught us, our overall well-being is far more important than any skill or event that we might desire to fulfill. Sometimes, pressing pause is the best thing we can do for ourselves.

Coming back from injuries

When you eagerly work on a new skill, and you get injured, fear takes on a whole new meaning. A big injury can set you back for months or even years. Worse, it can stop you in your tracks from further pursuing your gymnastics potential.

I’ve written about so many recoveries that I’ve dedicated a special section about it on this blog called Managing Injuries. The older we get, the more long-term those recoveries become. Despite that, it is possible to return to the activity we love, even when the injury happened there.

Strategic use of our wise mind at the gym allows us to steer our natural fear responses in the direction of healthy progress.

Love this! Then, of course, after the fear is conquered, the gymnast proceeds to let it all go and falls off the mat. 🤣

LikeLike

Yeah..it’s certainly not a perfect system…

LikeLike